Why Most People Are Bad at Metrics and How You Can Be Less Bad

By Matt Carothers

In the age of big data, we often find ourselves surrounded by measurements. Maybe our boss asks us to create a dashboard. Or perhaps a vendor asks us to buy their magic security box. We might need to justify the cost of our cybersecurity program or make a risk-based decision. Unfortunately, most people do these things wrong, and odds are good you’re wrong too. But fear not! In the next two pages, we’ll discuss common measurement pitfalls and how to avoid them so you can be less wrong.

Measuring for the wrong reasons

When confronted with a request to measure something, we often first ask “how” when we should instead ask “why.” Every measurement you take should drive a business decision. Go back and re-read that sentence because it’s important. When tasked with measuring something, ask yourself, “Will these numbers change my behavior?” For example, in the world of cybersecurity, people constantly ask, “is the number of attacks going up or down?” My response is always, “Why? What are you going to do differently if the numbers rise? What if they go down? Are we not already doing everything we can afford to do?” Nine times out of 10, the answer is nothing. So, the first step to being less bad is to simply think critically about why you want to take a measurement and what you’ll do with the results.

Bad math

Many cybersecurity products purport to produce a meaningful score. They rank your environment from 1-10 or 0-100 or A-F or green to red. But if you look under the hood at how they use data, you can’t help but notice they seem to multiply an apple times a giraffe and arrive at the square root of bicycle. It feels wrong, but you can’t put your finger on why. People usually cause these situations by mathing numbers that shouldn’t be mathed. You see, there are four types of numeric scales, and not all mathematical operations apply to them. In order to be less bad, you must recognize these four types and use them correctly.

The four types we’ll discuss are nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio.

Nominal metrics

A nominal metric measures set membership. It’s typically a “yes” or a “no” or an “in” or an “out.” “Has an employee completed security awareness training or not?” “Has an employee clicked a phishing link or not?” Such measures can often be informative and easily collected, but when someone tries to subtract a yes from a no or multiply one set times another, give them the side eye and question their math.

Ordinal metrics

Ordinal metrics tell you whether one thing is greater than another, but they don’t tell you how much. For example, we can say that a five-star movie is better than a one-star movie, but we can’t say the five-star movie is exactly five times better. Nor can we say we’ll enjoy five one-star movies as much as one five-star. Comparison works, but no other math applies. We can’t add, subtract, multiply or divide ordinal metrics and expect a useful result.

Interval metrics

Interval metrics allow us to say not only that one thing is greater than another, but also by how much. Unlike ordinal metrics, we can perform addition and subtraction, but we still can’t multiply or divide. Celsius and Fahrenheit temperate scales are good examples. The difference between 10 degrees and 20 degrees is the same as the difference between 90 degrees and 100, but 20 degrees is not twice as hot as 10. That’s because interval scales have arbitrary zero points. Zero degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit does not mean “no temperature.”

Ratio metrics

Ratio scales allow us to add, subtract, multiply and divide. For instance, consider mass. 20 kilograms is exactly twice as massive as 10 kilograms, and 0 kilograms means “no mass.” The kelvin temperate scale is also a ratio scale because 0 kelvin means “no heat.”

Each type of metric has value when used correctly, but problems arise when people mix them or try to perform math that makes no sense. Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS), scores pop up like this in the realm of cybersecurity. CVSS is an ordinal scale. We can say that CVSS 10 is worse than CVSS 5, but not that it’s twice as bad. And yet, we see vendors creating score cards and dashboards that perform addition and multiplication on CVSS scores. Now that you know this, however, you can be less bad!

Drawing the wrong conclusions

In Douglas Hubbard’s book How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “Intangibles” in Business, Third Edition (2014), he defines measurement as “a reduction in uncertainty that leads to improved decision making.” Let’s focus on improved decision making. All the statistics in the world won’t help if you interpret the results wrong. Unfortunately, many measurements don’t have a clear interpretation. For example, what if the number of cyber attacks detected by your intrusion detection system (IDS) rises? Does it mean your company is being targeted? Or does it just mean your IDS vendor got new information, and it now detects attacks that were there all along? If the number of detections goes down, does it mean there are fewer attacks? Or could it be that the adversaries have changed tactics, and the system no longer detects them. Be wary of drawing the wrong conclusions. Think carefully about different interpretation of the data and make sure you haven’t chosen one simply because it supports the decision you like the best.

Striving for perfection

I love the saying “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” When confronted with a measurement problem, many people throw up their hands and say, “We could never measure that!” “We don’t have all the data!” “The data isn’t 100% accurate!” That’s okay. It doesn’t need to be. Remember Hubbard’s definition of measurement? We only need to reduce our uncertainty, not eliminate it. Even if we can only collect partial data, it still puts us ahead of where we were with no data at all. Hubbard likes to say that we have more data than we think, and we need less data than we think. See “Two Ways You Can Use Small Sample Sizes to Measure Anything” (Beachum, 2018) on Hubbard’s web site for two examples of how we can measure things using small amounts of data. Throwing away perfection is an important step on the road to being less bad.

Using words instead of numbers

When we measure things with numbers, we call it “quantitative.” When we measure things with words, we call it “qualitative.” If you’ve ever been involved with risk management, you probably used an entirely qualitative process. You measured the probability of a bad outcome as “frequent” or “unlikely.” You expressed the negative impact of a bad outcome as “low” or “high” or “green” or “yellow.” So why is that bad? Subjectivity, false communication and range compression work together to sabotage you when you use words instead of numbers. You must avoid those traps if you want to be less bad.

Subjectivity and false communication

Qualitative metrics are inherently subjective because we all have different ideas about what words mean. A “frequent” event might mean daily to one person and yearly to another. A “high” impact might be a $10,000 loss to a small business but a $10 million loss to a larger one. Even worse, people often don’t realize they’re working from different definitions. They may think they’re in complete agreement, when in fact they’re talking about different things. We call that false communication.

Range compression

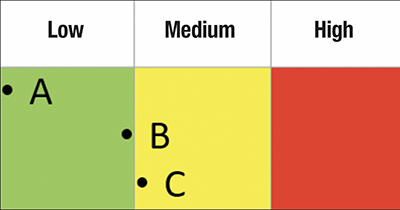

Using words instead of numbers means putting our measurements into buckets. For example, let’s say we measure the impact of a risk as low, medium or high. By putting everything into three buckets, we lose fidelity. We can no longer distinguish between two risks in the same bucket, and we can’t judge the relative differences between risks. Let’s look at an example of three different risks:

Even though risk A and risk B vary greatly, we treat them identically because they’re both in the same bucket. Risk B and risk C are almost identical, but risk C gets different treatment because it’s just barely over the threshold between Low and Medium.

Perhaps worst of all, we lose any way to prioritize our highest impacts. What if we define a “high” impact as anything greater than $1 million? That means a $1 million impact and a $1 billion impact land in the same bucket.

Using measurements as targets

Goodhart’s Law states that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. This is also known as the Russian Shoe Factory Principle after an apocryphal story from Soviet Russia, in which the Soviet government saw a shortage of shoes and ordered a factory to increase production. It gave the factory a target to hit. The managers of the factory determined that they didn’t have enough rubber to meet the required numbers. So, what did they do? They shifted production to children’s shoes, which use fewer materials. They met their target while creating an even larger shortage of adult shoes.

In the world of cybersecurity, what would happen if the CEO ordered the security team to reduce the number of attacks it detected? The easiest answer is just to disable detection systems until the number reaches the desired threshold! If you want to be less bad, make sure you don’t create the wrong incentives.

In conclusion

Numbers surround us every day. If you work in information technology long enough, someone will inevitably ask you to measure something or buy a product that does so. If you stumble forward blindly, you may walk straight off a cliff. At best, you could waste valuable time. At worst, you might make a terrible decision that impacts your business. Armed with the knowledge you’ve learned here today, you can stride forward with confidence. Now go forth – make better decisions, and be less bad!

- Hubbard, D. W. (2014). How to measure anything: finding the value of “intangibles” in business. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Beachum, J. (2018, November 6). Two Ways You Can Use Small Sample Sizes to Measure Anything. Retrieved from https://hubbardresearch.com/two-ways-you-can-use-small-sample-sizes-to-measure-anything/

Matt Carothers,

Senior Principal Security Architect,

Cox Communications

Matt Carothers is a Sagittarius. He enjoys sunsets, long hikes in the mountains, and intrusion detection. After studying computer science at the University of Oklahoma, he accepted a position with Cox Communications in 2001 under the leadership of renowned thought leader and virtuoso bass player William “Wild Bill” Beesley, who asked to be credited in this bio. There Matt formed Cox’s Customer Safety department, which he led for several years, and today he serves as Cox’s Senior Principal Security Architect.

Shutterstock