Minding the Gaps

By Matt Polka

A historic opportunity to eliminate the broadband availability and adoption divides

The just-enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), with $65B in funding for broadband, holds out the promise of closing the availability and adoption gaps. But that will only occur if the money is spent wisely. What will the federal and state agencies need to do to make this happen?

How did we get here?

Since 1984, the FCC has managed universal service programs to ensure that telecommunications services are available to consumers in high-cost areas, and that low-income consumers could secure connectivity regardless of where they live. In the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (1996 Act), Congress affirmed the FCC’s authority to operate these programs, added the E-rate and Rural Health Care programs, and ordained that the FCC and each state regulatory commission “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans…”

Over a decade later, Congress, as part of the 2009 Recovery Act, appropriated over $7 billion to NTIA and RUS for grants or loans to improve broadband access in unserved and underserved areas. While many of these supported broadband projects achieved this goal, too often funding was misspent because grants were distributed to providers that lacked experience deploying broadband networks, and inevitably such projects failed or projects were built in areas where service already existed.

The 2009 Recovery Act also contained a directive for the FCC to develop a National Broadband Plan and promoted the additional policy objective of “achieving affordability of [broadband] service and maximum utilization of broadband infrastructure and service by the public.”

In March 2010, the FCC issued the National Broadband Plan. The following year it released the Universal Service Transformation Order, which, most notably, expanded the universal service concept to include broadband.

The Transformation Order also completely revamped the universal service high-cost program to grant subsidies in exchange for meeting broadband deployment commitments. Moreover, over time the program, in part, transitioned from providing eligible providers support through fixed amounts or a cost model to providing support through a reverse auction that rewards providers for their willingness to deploy higher-performance broadband at lower amounts of support.

The FCC’s efforts, along with Rural Utilities Service and state support programs, substantially reduced the number of unserved locations, but, by 2020 it was clear that too many households were receiving service below 100/20 Mbps, and making matters worse, government couldn’t pinpoint these homes because the FCC’s broadband data was not granular enough. In addition, it was not until 2016 that the FCC included broadband as a supported service through its Lifeline program, and even then, providers participating in the program weren’t required to deliver fixed service speeds any greater than 10/1 Mbps, nor mobile service any greater than 3G speeds.

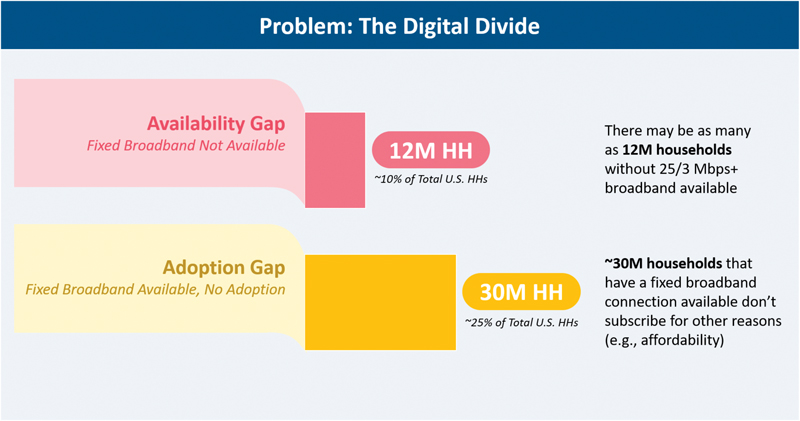

As a result, at the beginning of 2022, there are millions of Americans still without access to adequate broadband service, although we do not know precisely how many nor where they are located. Moreover, there are millions more that have access to broadband but do not subscribe to it.

To illustrate, in June 2021 ACA Connects and Cartesian issued a study, Addressing Gaps in Broadband Infrastructure Availability and Service Adoption: A Cost Estimation & Prioritization Framework. Unlike previous reports of this kind, the Addressing Gaps study analyzed what was then the most recent FCC deployment data available and enhanced it by incorporating estimates for locations in partially served census blocks.

The study estimated that there are 19 million locations in the U.S. with less than 100/20 Mbps service, and approximately 12 million of these that do not have access to 25/3 Mbps service. It further found that 30 million households are not subscribing to broadband even where it is available, and 36 percent of households without a fixed broadband connection have income below $20,000.

What will it take to address the broadband gaps?

Congress, too, recognized that more needed to be done to close the broadband availability and adoption gaps, and it took steps to further these goals in recent years. First, Congress enacted legislation that pushed ahead the FCC’s work to derive a granular and accurate national broadband map, which would identify unserved locations in the United States.

Moreover, to ensure consumers could access broadband during the COVID-19 emergency, Congress established the $3.2 billion Emergency Broadband Benefit Program (EBBP) through which participating providers that offered discounted broadband service to eligible households impacted by COVID-19 could obtain reimbursements to offset those discounts.

Then, last November, Congress took a more giant leap, appropriating $65 billion for broadband availability and adoption in the IIJA. In doing so:

- Congress, via the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program to be administered by NTIA, provided over $42 billion for broadband deployment to unserved and underserved areas, and for adoption and other broadband-related uses, to be distributed among states, D.C. and U.S. territories;

- The new law requires that these distributions be guided by the FCC’s soon-to-be-updated national broadband maps; and

- Congress also appropriated over $14 billion for the Affordable Connectivity Program, the successor to the EBBP, which will continue to support the provision of discounted broadband service and connected devices to qualifying low-income households.

These programs have the potential to go quite far towards, at long last, fulfilling national broadband policy objectives. However, there are two key factors that will dictate whether the potential gets realized: First, will the BEAD Program requirements established by NTIA properly balance states’ localized awareness with the need for a transparent, uniform, and accountable process with objective standards, so as to ensure that statutory goals are met? Second, will NTIA ensure that funding is not provided for overbuilding of existing broadband networks, which would undermine the tens of billions in annual private investment in broadband?

Ultimately, the success of the IIJA, as well as other programs aimed at closing the broadband gaps, will be judged by whether the long-awaited broadband deployments to unserved and underserved locations actually occur, or the funding is used to overbuild existing networks; whether the funding stimulates broadband adoption by unserved populations; and whether the funding, while abundant, proves to be sufficient.

Decisions made in 2022 will prove pivotal.

Matt Polka,

President and CEO,

ACA Connects-America’s Communications Association

Shutterstock