How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All?

By Jeff Finkelstein

As the apocryphal proverb goes, “May you live in interesting times.” When the original author first said it, whomever they may be and whenever they said it, I would bet dollars to donuts they did not say it with the current state of the service provider industry in mind. From the origination of DOCSIS and PON, to today, we have seen mind-boggling growth in customer bandwidth demand and ever-increasing bandwidth supply availability.

Over the years we have seen not only dramatic growth in capacity, but also consumer demand. It is demand which we have no control over. We do have control over how much supply is available to a specific serving area. There are as many ways of planning for future growth as there are operators, but in the end we all calculate a compound annual growth rate, which we use to plan for future growth needs.

Set your WayBack machine to the 1990s when consumers were discovering cable modems. For many a 1 Mbps speed was blazingly fast compared to a 56 kbps dial-up modem. Now we have speed offerings up to 2 Gbps downstream and 1 Gbps upstream. The interesting thing to me here is not that we have made such a quantum leap in supply capacity, but that consumer demand has changed so dramatically from what we projected as we were growing.

Remember around 2006 or so when Sling was released? Our downstream and upstream CAGR was running at 40% or more. I remember folks talking about how companies would need to leave the service provider space as we could never keep up with the demand. Our CAGRs, which once were at the 40% threshold, are now down to between 10% and 20%. In some cases, less.

So, what changed? A rhetorical question as we know nothing has changed except the user’s consumption habits and total available capacity. In general, not only has the delivery system increased in size, but the consumers have increased in numbers and knowledge.

Ya, but so what?

The “so what” is we have inverted the model from a demand-based system to a supply-based one. We have enough supply with what is available today, whether DOCSIS 3.1/EPON/XGS-PON, to last us a long time. A very long time. Possibly 10 to 15 years. However, we know that it takes about that long to bring out newer technologies at scale. Every technology requires standards or specifications development for broad acceptance, but that is only one piece of the puzzle. To take a technology from ideation, creation, specification, testing, lab and field trial, then finally deployment, takes a lot of coffee and other beverages.

There have been numerous attempts to shorten the cycle, but so far none has been truly successful. Things end up getting caught in the maelstrom created when you skip important steps or do not get buy-in by the companies that need to be involved. While we may convince ourselves that we can push things through by sheer willpower, the reality is no matter how good the technology appears, it requires people to believe in it. No technology can exist for long in a vacuum.

The constant innovate, create, use, improve, recreate cycle takes time, people, and money. However, the first thing companies do when financially challenged as we have all been since the pandemic, is to reduce spending in what is considered as non-essential areas. R&D is typically one of the first to be cut. A fiscally conservative approach requires hard decisions, ones that force executives to make hard decisions. It is our job as scientists and engineers to add a touch of prudence to that process.

Technology lifecycle is the new black

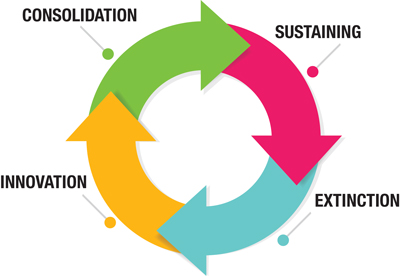

There has been much written about product lifecycles, but I believe technologies have their own unique lifecycle. The more I pondered this I realized that there is more to it. I talked to quite a few folks about this and now consider technology as in one of four stages. There is no sharp cut-off between them as it typically happens organically.

Stage 1: Innovation

The innovation stage is as we expect. Someone comes up with an idea to solve a problem, or a problem to solve an idea. They pitch it, modify it based on inputs, and in the end, it looks like something new. It requires investment not only to create the concept, but also to create the first generational products.

Once the initial products have been vetted there is a mad rush from smaller companies to join the party. Think back to the early days of DOCSIS: We had many companies making cable modems and CMTS, which today have been reduced to numbers you can count on one hand.

Stage 2: Consolidation

The very act of having many companies fighting for a piece of the pie means that the piece everyone gets is smaller. Some of those companies merge or get acquired by others, or simply go the way of the dodo and vanish. This leaves some customers out to dry as they no longer can get support for the products they purchased.

Companies that have acquired the resources of others do so for many logical reasons. Whether for improved technologies, people, new markets and customers, or other reasons, they now must manage these new larger organizations. Too many learn too late that they are not structured to handle the complexities created by the new organization. This results in challenges maintaining products, creating new technologies, and keeping staff.

Stage 3: Sustaining

Once things have settled down a bit, we get into the daily grind of deploying and maintaining these technologies. We are not thinking about creating new technologies as much as we are trying to figure out how to eke every bit per second per hertz out of what we currently have available to us.

As the data services we provide to our customers become critical and necessary, we are required to be ever vigilant in the maintenance of our assets. That means time invested, money spent, and people trained in keeping things humming along.

What ends up missing is the reinvestment in what comes next or next next. To come up with the next big thing, we are required to go back to stage 1 and innovate. It can come from outside our organizations, but without our input it is just another shiny object that looks nice but ends up on the shelf with other shiny objects.

Stage 4: Extinction

If we do not make that investment, our technologies are eventually going to become extinct. While we can sustain a given technology for a long time, we cannot sustain it indefinitely. At some future time, most likely driven by Murphy’s Law, it will occur when we can least afford to have it happen.

Without having a next generation to guide us, we can only keep using what we currently have, as we always have, which gets more expensive over time. Fortunately, we have the luxury of time, at least for a while.

Not that extinction of a technology is a bad thing. We have the tendency to use some technologies far longer than we should. There are times when the money we spend to keep a technology limping along would be better spent on developing its replacement.

Conclusion?

As Jeff’s Rule #37 states:

Technology does not drive the path, the path drives the technology. We need to have a long-term strategic goal, more so than just keeping up with the competition. Whether we are driven by new product offerings, reduced costs, consumer services, or other reasons, technology requires a problem to solve.

And remember Jeff’s Rule #65 which states:

The wrong thing at the right price is still the wrong thing.

Jeff Finkelstein,

Jeff Finkelstein,

Chief Access Scientist,

Cox Communications

Jeff Finkelstein is the Chief Access Scientist for Cox Communications in Atlanta, Georgia. He has been a key contributor to engineering at Cox since 2002 and is an innovator of advanced technologies including proactive network maintenance, active queue management, flexible MAC architecture, DOCSIS 3.1, and DOCSIS 4.0. His current responsibilities include defining the future cable network vision and teaching innovation at Cox. Jeff has over 50 patents issued or pending. He is also a long-time member of the SCTE Chattahoochee Chapter and member of the Cable TV Pioneers class of 2022.

Images provided by author, Shutterstock