Can Cable Be Cool Again?

By Stewart Schley

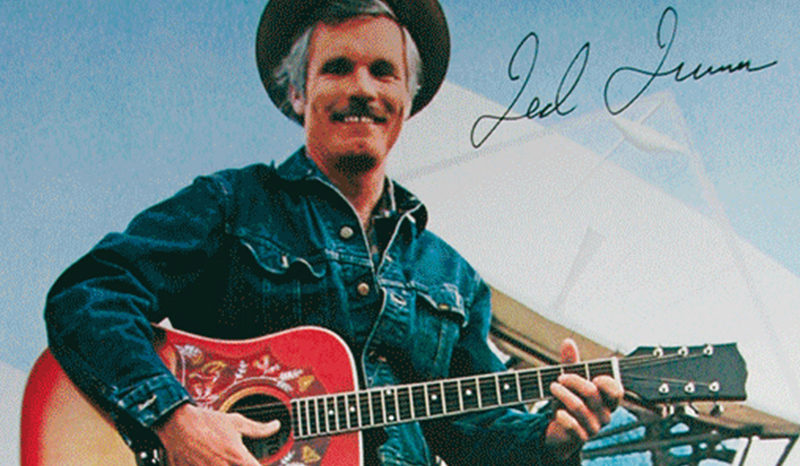

IN A 1982 TRADE MAGAZINE ADVERTISEMENT, THE CABLE INDUSTRY PROGRAMMING IMPRESARIO TED TURNER STANDS IN A HARD-SCRABBLE FIELD, DRESSED IN DENIM JACKET, BLUE JEANS AND COWBOY BOOTS. HE’S STRUMMING A GUITAR IN FRONT OF FOUR WHITE SATELLITE DISHES SPROUTING FROM THE EARTH BEHIND HIM. THE AD’S HEADLINE IS A PLAY ON THE 1981 BARBARA MANDRELL COUNTRY-MUSIC HIT: “I WAS CABLE WHEN CABLE WASN’T COOL.”

The Turner Broadcasting System founder was displaying his industry bona fides in response to a competitive affront from a new network called the Satellite Newschannel, which for a brief time challenged Turner’s CNN and its offshoot, Headline News. Turner was reminding people he had bet his company on the emerging cable industry years before other large media companies — in this case the broadcasters Group W and ABC — piled on.

What’s interesting about the marketing theme 36 years later is the underlying pretext: that cable was unquestionably, avowedly “cool.” It was an article of faith that provoked little argument. By the early 1980s cable was growing like mad both economically and technologically. Twelve-channel community antenna TV services had morphed into 35-channel (and greater) wellsprings of new television possibility. Cable had given the world CNN and HBO, had dreamed up concepts like the QUBE interactive-TV platform, and had figured out a way to harness the transformative power of satellite communications. In August of 1981 the industry spawned the TV channel that was coolness personified: MTV: Music Television.  Enthusiastic young adults fresh out of college and angling for a media industry career gravitated to the industry that had taken the stodgy world of broadcast television and turned it upside down. Cable was a place where ideas were welcomed, the slate was blank and the opportunities just about everywhere.

Enthusiastic young adults fresh out of college and angling for a media industry career gravitated to the industry that had taken the stodgy world of broadcast television and turned it upside down. Cable was a place where ideas were welcomed, the slate was blank and the opportunities just about everywhere.

“It was the kind of industry where you could just raise your hand and say, ‘I’d like to try that,’” says Jana Henthorn, a cable industry veteran who began her career in 1983 with Time Inc.’s cable subsidiary and is now president of The Cable Center in Denver. Bob Gold, a veteran public relations executive who began his cable career with the Cable Health Network in the early 1980s, says cable’s early-era entrepreneurial spirit was palpable. “We were making something happen that had never happened before. We were Silicon Valley before Silicon Valley was super cool. We were Facebook, Netflix and Google before they existed.”

Modern maturity

And then, to steal a title from the late novelist Joseph Heller, something happened. Over the next two decades, the cable industry would begin to creep toward maturity, undergo dramatic ownership consolidation and, in the eyes of some participants, lose some of the entrepreneurial luster that had once made it such an attractive career pursuit. As household penetration reached 50 percent in 1987 and rose from there, cable went from upstart newcomer to a taken-for-granted staple of the American media experience. By the late 1990s nearly everybody had cable TV or a competitive alternative like satellite TV that largely mimicked the cable video model: lots of channels, old-fashioned grid-style guides, balky pay-per-view services.

It wasn’t that cable lacked innovation. The introduction of fiber optics, the invention of video-on-demand, the breakthrough that was DOCSIS, the halts and stumbles around interactivity and the embrace of high-definition signal delivery all advanced the industry’s innovation pedigree into the early 2000s.

The problem from a perception standpoint, however, was that by the late 1990s all the really cool stuff seemed to be happening somewhere else, on a platform called the Internet.

There was Napster, e-bay and portals-to-anywhere like Google and Yahoo! There were photo-sharing tools that changed the way people shared visual images. There were chat rooms. There were file downloads. There was the halting but promising arena of streaming media. Kids could play live, interactive video games with opponents across the world. Screens became mobile and video became digital. The bulky brick phones of the 1980s gave way to thin, portable computing devices with tremendous processing power and always-on connectivity. Then, in 2007, while cable watched from the sidelines, a company that had made a living mailing DVDs quietly launched a video streaming service called Netflix Watch Instantly, which would completely change cable’s world.

The irony wasn’t lost on the cable industry: It was the broadband infrastructure cable brought to scale that replaced the dial-up Internet connections of old and ushered in one stupendous innovation after another. But nobody seemed to give cable much credit. “I don’t think there’s a high schooler in America who might recognize that cable invented and delivered broadband,” laments Gold.

Instead, the admirers looked west. Whip-smart, tech-savvy graduates dashed off resumes to Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Netflix, giving little thought to making their mark in an industry that some believed had become staid, predictable and even boring. Industry veterans worried behind closed doors about how their industry had come to be seen as a something akin to a utility, not a source of innovation. Right or wrong, cable, once a powerful disruptor of the media industry establishment, had become everything it never was. It had become The Man.

“It was something everybody talked about,” recalled Peter Kiley, a C-SPAN vice president who has watched the industry develop since he began working for the public affairs network in the early 1980s. “That we were no longer the cool place to work.”

But lately, Kiley and others think perceptions might be changing, thanks to the latest iteration in a long run of industry reinvention. Before addressing an inaugural group of graduates from The Cable Center’s new Intrapreneurship Academy recently, Kiley talked with me about how the cable industry’s embrace of a digital-first mindset has reinvigorated interest among young, tech-savvy job candidates. Kiley pointed to Comcast’s creation of the X1 digital media environment as one indicator. The interactive media platform is a symbol of Comcast’s transformation to a software-centric company. So is Comcast’s new 60-story, $1.5 billion downtown Philadelphia office building that houses “a growing workforce of technologists, engineers, and software architects.”

Something similar is happening in suburban Denver, where the nation’s second-largest cable provider Charter Communications is actively recruiting UI designers, code writers, prototype developers and technology specialists to join a 2,000-person engineering and technology team focused on advanced digital technologies. Don’t tell Google, but there’s a big concentration on recruiting whiz kids who can create and support mobile apps — you know, just like the kind they invent in Mountain View, Calif. At a hip new building bedecked with exposed concrete and high ceilings, Charter also has lifted a perk straight from the Silicon Valley employee recruitment handbook: Foosball tables.

Partly because of the industry’s new embrace of software-powered products and services, “Cable’s as cool now as it has ever been,” said Kiley.

He may be onto something. Young professionals like 24-year-old Jordan Florschuetz, a Charter product manager in Colorado, are happily going to work in an industry they once dismissed. “I’m a cord-cutter. I never thought I’d work for cable,” said Florschuetz, who manages customer self-service features of Charter’s online portals. But an internship opened the Colorado State University graduate’s eyes to a wide-open future for cable companies. “We own the network; it’s a huge asset,” she told me. “Assumptions are that by 2020 the average customer is going to have 50 devices connected to their home network.” That, plus the fact that cable’s broadband networks are powering new ways of watching video, have her convinced cable’s the place to be.

The Cable Center’s Henthorn wants to build on these changing perceptions. In focus groups she conducted with millennial-generation participants, Henthorn was struck by the disconnect between what industry employees think about the cable industry, and what their outside-the-industry peers believe. “The younger employees love this industry, think it’s very cool and very innovative, but their friends are asking, ‘Why are you in the cable industry?’ Henthorn explains. One way to bridge the perception gap over time, she thinks, is to encourage innovation from within. The Cable Center’s Intrapreneurship Academy is a nine-week immersive education curriculum conducted twice annually, with contributions from prominent industry figures. (Participants have included Comcast’s original CFO Julian Brodsky and cable industry programming veteran Evan Shapiro). It’s designed to help new hires and rising stars (Charter’s Florschuetz is one recent graduate) find ways to champion innovation from inside-out by influencing risk-taking, product development and idea generation within their own organizations. It’s a different approach to entrepreneurialism than the one that prevailed in cable’s go-go years, when lots of companies made up the industry, but Henthorn says the “intrapreneur” concept is well-suited for an environment where great ideas still rule even though consolidation has changed the industry’s makeup. “If you’re willing to raise your hand and try something new,” says Henthorn, “this industry’s there for you.” That alone might help elevate cable’s coolness factor.

And Speaking of Cool …

AS THE CABLE INDUSTRY ENTERS A NEW ERA OF DIGITALLY DRIVEN PRODUCTS AND SERVICES, THE HUMAN BRAINPOWER THAT DRIVES INNOVATION HAS TO REV UP TO MATCH THE INDUSTRY’S TECHNOLOGICAL AMBITION.

THANKS TO SCTE•ISBE, THAT’S HAPPENING IN A BIG WAY.

The organization’s new Cortex Expert Development System draws on new scientific methods of learning and development to create game-changing advances in knowledge and information retention within the technical workforce. Applying proven techniques for stimulating brain function, the Cortex system raises the bar for knowledge attainment and memory that translate to a better-educated, more capable, more knowledgeable workforce.

Powered by mobile digital apps, Cortex applies the latest proven approaches to dynamic learning to take employees beyond understanding concepts to mastering concepts. It’s an approach today’s sophisticated, demanding workforce candidates look for in their employers, whether they’re cable operating companies or technology partners. Today’s best candidates want to attain mastery, improve their skill sets and fully participate in the digital economy. The Cortex Expert Development System helps them do it, faster and better. That’s the definition of cool.

Want to find out more? Download Cortex Mobile by searching for SCTE•ISBE CORTEX in the App Store or Google Play. Learn more at scte.org/cortex.

Stewart Schley,

Stewart Schley,

Media/Telecom Industry Analyst

stewart@stewartschley.com

Stewart has been writing about business subjects for more than 20 years for publications including Multichannel News, CED Magazine and Kagan World Media. He was the founding editor of Cable World magazine; the author of Fast Forward: Video on Demand and the Future of Television; and the co-author of Planet Broadband with Dr. Rouzbeh Yassini. Stewart is a contributing analyst for One Touch Intelligence.

credit: Shutterstock.com