Art and Innovation

By Jeff Finkelstein

Art Imitates Life

As a member of our local art museum, I recently attended the gala opening of a new exhibit featuring Andy Warhol prints. I spent hours wandering through the rooms, often going back and revisiting previous rooms, to help put things in context and better understand where his abilities took him.

The rooms containing the artwork were decorated by local artists with quotes from Mr. Warhol. One quote stood out as I walked through the exhibit:

“They always say time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself.”

— Andy Warhol

This quote resonated with me as I try to figure out how future consumer needs will drive our technologies, then work to tell a compelling story so others will help solve them. Being a visionary is hard as you need others to buy into your vision. It is especially hard when you miss a trend.

It is amazing to consider how over the past 50+ years the technologies in the service provider space have changed. Technologies have made quantum leaps thanks to silicon improvements, which made possible things like the desktop computer, smart phone, Apple watch, autonomous cars, and even DOCSIS itself.

In my last article, I discussed briefly the concept of corporate anti-bodies that try to shut down attempts to advance technology which may solve problems that do not exist yet. If we relied solely on those individuals to make the decisions, it is unlikely things would have moved at the incredible rate of change we have seen in many industries, including ours.

There is No “I” in Team

Innovation is hard. Innovation is lonely. Innovation is simultaneously uplifting and depressing. Innovation is not for those that don’t like to fail.

Without individual involvement in innovating we are only passengers on the time-space continuum of technology transformations. If you are content to wait for things to change you are automatically behind the curve of others willing to take the risk. It is only by participating as an active member of the innovation community that we may help the brilliant innovators out there to focus on real-world business problems that may not exist for years.

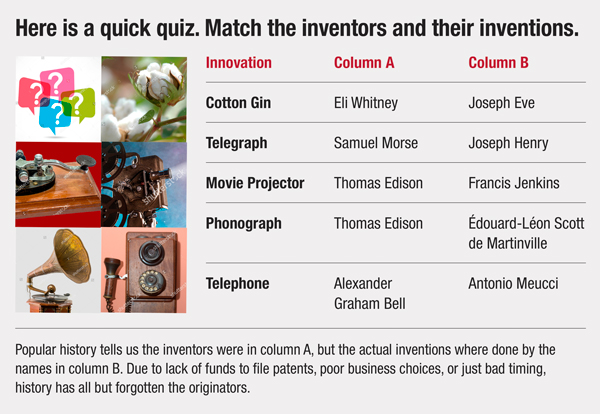

While the initial spark of generating ideas is typically a solo effort, to take innovative concepts from idea to execution is a team sport. It often happens that the originator of new ideas is lost in history. If you want to play in the innovation space it is something you must understand and come to terms with being left out once it is handed off to others.

At Cox, in addition to my pondering the future of the service provider networks, I lead a workshop on innovation for the technology organization. Briefly, how it works is that anyone in the organization can submit their ideas for consideration, then the top 10 or so are brought to our corporate offices for a two-day workshop. In that workshop, we teach them about innovation and how to present their ideas to executives for funding. While the initial spark comes from solo-storming, it takes a team to deliver that idea to reality. We have had good success with this approach and while not the focus of this article, I would be happy to chat about it off-line if you are interested.

Then why write about innovation? It is not about just the successes, it is about how we choose to fail.

Failure is Not an Option, It is Our Only Option

“Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan.” — G. Ciano

In the innovation space, you must own your failures and be willing to give your idea to others for execution. This is a method for clearing space in your mental synapses for new ideas.

We work in companies focused on operational efforts that provide services to our customers which make a difference in their lives. There is very little margin of error for these services that have become a significant value to them. A 99.999% success rate at operational efforts is considered success, but a 10% success rate in innovation is excellent. Yet, it is often difficult to reconcile these two within our organizations. Measurements and metrics are extremely important to operational efforts, but they may reduce our acceptance of the chances we must take to succeed with innovative thought.

I remember a yearly review from the past, where my manager at the time told me he didn’t know how to rate me as I only accomplished three out of 10 items on my “to-do” list for the year. My response was I did not complete three and fail at seven, I intentionally chose not to do those seven. By choosing to focus my team on the top three items and moving the other seven to the “to-don’t” list, we succeeded with little wasted effort on those things that had little chance for success. We should not measure innovation efforts just by the successes, but also by those things we chose not to do.

After 22+ years of being in cable I have personally, and as part of larger teams, been involved with creating a few different technologies. As we worked through refining problem statements and possible approaches to solving them, I realized that the initial spark of creating a technology is based on our perception of the problems we are trying to solve. Our varied background and experiences color how we solve for “X,” which gives us the opportunities to learn from each other and opens discussions on our unique approach to the problem. If we always solve problems from the same viewpoint, all our solutions tend to look alike.

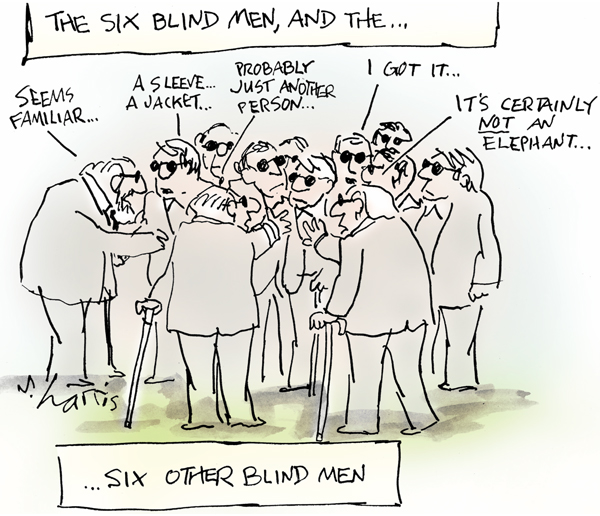

By example, if you take six blind men and put an elephant in front of them, their impressions will be based on where they are in relation to the elephant. Unless of course, there is no elephant…

It is those individual and original viewpoints that are the value-add we all bring to the discussion with our varied backgrounds and approaches. If we only ever have one viewpoint, then we may miss the bigger picture. Diversity of backgrounds in future thinking is critical to finding solutions to problems where we may have a limited field of view. Without seeing, hearing, and openly considering the innovative thoughts of others, every solution eventually looks alike.

Put another way, if you are old enough you might remember the original text-based adventure game, “YOU ARE IN A MAZE OF TWISTY LITTLE PASSAGES, ALL ALIKE.”

The Value of Simple Things

For many years, I have been collecting concise sayings (or as I call them “the rules”) I heard, or personally said and/or wrote, that resonated with me and could be applied to our industry. My plan for this and future articles, is to discuss these sayings and their applications. Hopefully some will be of value to you as you think about technology.

Starting with simplicity…

Rule #1: Make things as simple as you can, but not simpler (possibly said by Albert Einstein, but the true origin is unknown).

It is so easy to fall in love with our own ideas. They are our children. We participate in their birth, help them mature, teach them, tell others how brilliant they are, and watch them grow up. Like our own children, it is not until we let them go that we know how well they will stand on their own two feet. It is our responsibility as parents (innovators) to help prepare them for the journey ahead. We frequently do not know what is in store for them, so we do the best we possibly can. Still, in the end, it is up to each child (idea) to stand on its own and grow.

One of the key concepts I discuss in our innovation workshop is the “Zen” statement. We tend to use lengthy prose when talking about our big, beautiful ideas, and reducing each one down to a single sentence is hard work. What it does is force us to think about the idea in a different way. How do we distill the essence down to a single sentence? We do many exercises in our innovation workshop and this is the hardest concept for students to work through to completion. In the end, they understand that simplicity is essential for others to understand an idea. We cannot fall back into our comfy place of using techno-babble to amaze the audience with our genius. We are forced to compress and simplify down to the Zen of the innovation idea.

The skill of reducing complex concepts to simple statements is one that many of us are lacking. It is a lot like traveling. You want to pack enough in your luggage to get you through your trip, but if you pack too much you burden your entire travel and will likely not enjoy the destination. For me, even at this point of my career with over 2 million air miles, I still tend to pack too much. I know better, but it is a hard habit to break even today. I try limiting myself to a single duffel bag for a two-week trip and will do laundry if needed. I find that it is not the clothes that take up the room, it is all the other items for shaving, bathing, hair products (not in my case as it would be like pruning a dead tree), etc.

The same goes for our ideas. We want people to support them, so we use flowery prose to get the idea across. If you are a book reader compare Thomas Wolfe to Ernest Hemingway. What Wolfe says in 1,000 words is what Hemingway would say in 100. Use language as your tools and write crisply, concisely and succinctly.

Shaving with Occam’s Razor

Shaving with Occam’s Razor

To illustrate, let’s use Occam’s razor as an example. Most quote 14th century logician and Franciscan friar William of Ockham as having said in the original Latin, “Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem.” Which is roughly Google translated as

“If you have two equally likely solutions to a problem, choose the simplest.”

If we follow those over the decades who apply their own twist to his statements, we often end up with wording that is much stronger than what the good friar intended.

“If you have two theories that both explain the observed facts, then you should use the simplest until more evidence comes along.”

“The simplest explanation for some phenomenon is more likely to be accurate than more complicated explanations.”

“The explanation requiring the fewest assumptions is most likely to be correct.”

“If you have two equally likely solutions to a problem, choose the simplest.”

… or in the only form that takes its own advice…

“Keep it simple.”

Occam’s Razor works as a heuristic rule of thumb, don’t treat it as a law of physics the same as Newton, Galileo or Copernicus. It is not. Simplicity is subjective and the universe does not always have the same ideas about it as we do. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that once you found a simple answer then you are done. You must perform the wash, rinse, repeat cycle of analytics and analysis, plus talk to the very people that your solution will be helping, before you declare success and crack open a beer.

Serendipity favors the prepared. And while it is easy, waiting for a serendipitous event is not a plan. You must invest the time to make sure you are trying to solve the right problem, at the proper time, with the correct tools, that when told your potential customers causes them to go “Wow!”

When constructing and describing your idea, less is more. Choose your words carefully to make the most impact.

Art and Innovation

I started this article with the heading of “Art Imitates Life,” as said by the author Henry James in 1884. A contemporary of James and fellow author, Robert Louis Stevenson, responded with the statement “Life imitates Art.”

I believe that both are true and can be applied to innovation. In innovating new and unique uses of technology, the ideas come to life as an abstract concept that inhabit not the real world, but the minds of the inventors. It is only through the sharing of those ideas that they are brought to life.

As visionaries, it is our responsibility to not only come up with the scathingly brilliant ideas, but equally important are the right way to share them. If it does not inspire others, then take a hard look at both the innovation and your presentation of the problems you are looking to solve.

If people are not inspired by your ideas, stop and regroup. Come up with a new way of showing the value proposition in your thinking. Make it a better idea. It is a much more efficient use of time to improve your innovations and explanations than to push something that has no wheels.

As leaders in innovation, we must share purpose, pointing the way to a new reality.

We need a team to help us realize when required that “that dog don’t hunt.”

Jeff Finkelstein

Jeff Finkelstein

Executive Director of Advanced Technology

Cox Communications

Jeff Finkelstein is the Executive Director of Advanced Technology at Cox Communications in Atlanta, Georgia. He has been a key contributor to the engineering organization at Cox since 2002, and led the team responsible for the deployment of DOCSIS® technologies, from DOCSIS 1.0 to DOCSIS 3.0. He was the initial innovator of advanced technologies including Proactive Network Maintenance, Active Queue Management and DOCSIS 3.1. His current responsibilities include defining the future cable network vision and teaching innovation at Cox.

Jeff has over 43 patents issued or pending. His hobbies include Irish Traditional Music and stand-up comedy.

Shutterstock.com

Cartoonstock.com