50 Shades of Grey Optics: An SCTE•ISBE Expo Roundup of Nerdy

By Leslie Ellis

Summertime, for people who write and edit technical documents for a living, is a smorgasbord of nerdiness, because it’s when some of us — lots of us, actually — are up to our eyeballs in the words, equations and diagrams that become the meat of the SCTE•ISBE Cable-Tec Expo, in the fall. This year, 115 of them, and among them some seriously tasty nugs (that’s surfer-speak for “seriously good.”)

For that reason, this edition of Nerdy Little Secrets shall hone in a few concepts you’re likely to run into at this year’s Expo, scheduled to roll into New Orleans from Sept. 30 to October 3. Starting with the concept of “energy harvesting.” As a gardener, beekeeper, and (wishful) chef, I’m naturally attracted to harvests of many flavors — so imagine my delight to pore over a paper about energy harvesting, of all things!

It goes like this: A lot of the “things” of the Internet of Things (the IoT) are small — a sensor, designed to monitor something for a very long time, and send small amounts of data, relatively infrequently. Powered by batteries. Which die. But! Innovation is happening big time in the battery scene.

Turns out there are three ways to harvest power for small objects, like sensors: Conductive (achieved through a temperature difference between two surfaces), mechanical (achieved through motion/vibration), or radiant/electromagnetic. The latter comes stocked with impressively nerdy talk like “Schumann resonances,” which involve solar energy and the Earth’s natural electromagnetic field, in a sprightly spectral slice known as ELF, for extremely low frequency.

Anyway. It goes like this. Say you have a sensor on a wall switch, like a Zigbee. The action of pushing the switch generates enough mechanical energy to transmit a (one-way) message. Likewise for “shake flashlights,” where onboard magnets and wire coils, activated by a mechanical motion, can induce a current sufficient to light an LED. (Both examples remind me of a wristwatch my paternal grandfather used to wear, which got its power when he shook his wrist; otherwise, and with all other watches he wore, the battery died within a week. I carry the same genetic wiring.)

And let us not forget the power of the “supercapacitor,” super because it has a capacitance measured in farads, as opposed to picofarads and microfarads used in most electronic circuits. And thank you, Ron Hranac, for the clarity, harvested from a Facebook post which asked: What’s super about a supercapacitor? Turns out Ron’s outdoor weather instruments use a combination of battery, solar cell and (10 farad) supercapacitor — so that when the sun goes down, the supercapacitor can take over, backed up by the battery if necessary.

More harvest-related nerdy: The “nantenna,” for nano-antenna, so named because it uses silver (not silicon) to harvest solar energy, and the MEMS Pyrotechnic Capacitor, where “MEMS” stands for micro-electrical-mechanical systems, and is used to harvest residual heat to power things like USB ports.

Other impressively nerdy Expo techtalk: A new one on me, “grey optics.” (Not sure if it’s going to happen, but in editing one Expo tech paper, I recommended a shift in title to “Fifty Shades of Grey Optics: A Roadmap for Next Generation Access Networks.”) What’s grey about grey optics, you ask? I did too. It’s a backhanded linguistic nod to other types of optical systems, like WDM (wavelength division multiplexing), that use specific light “colors,” or “wavelengths,” in optical-talk; “grey” essentially means “uncolored,” and is a euphemism for a standard, easy-to-acquire, low-cost optical transceiver.

Grey optics hover around conversations about gigabit-grade capacity. It exemplifies the march of innovation from long-haul networks, directly into edge networks. And — because network edges differ! — by “edge,” I mean hybrid fiber/coax (HFC), and the current events happening there — like pulling the “F” part, fiber, deeper into neighborhoods.

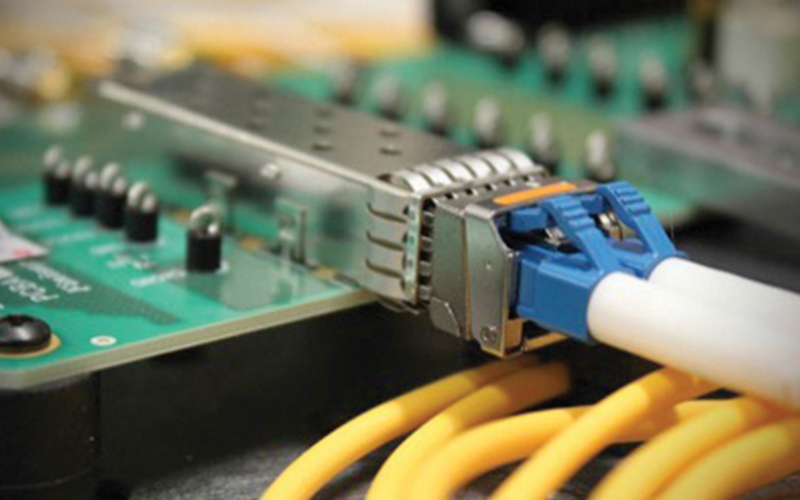

With grey optics come little gizmos called “SFPs,” for “small form factor pluggable” optical modules, attaching deep in the HFC plant. SFPs represent a massive miniaturization of gear that used to be housed in racks (plural) much “higher up” in the network than the last mile. All of it matters to the introduction of packet switching at the network edge, which matters to things like gigabit services.

And that’s just a few of the topics I’ve had the good fortune to sneak preview, the hard way, as a front-end editor of our industry’s tech-side brain trust. Now where’s that big bag of commas?

Leslie Ellis,

Leslie Ellis,

President,

Ellis Edits Inc.

leslie@ellisedits.com

Leslie Ellis is a tech writer focused on explaining complex engineering stuff for people who have less of a natural interest than engineers. She’s perhaps best known (until now!) for her long-running weekly column in Multichannel News called “Translation Please.” She’s written two broadband dictionaries, one field guide to broadband, and is a behind-the-scenes tech translator for domestic and global service providers, networks, and suppliers. She’s served as board member of the Rocky Mountain chapter of the SCTE since 2015, and is a 2019 Cable Hall of Fame inductee.