The Subtitle Goes to School

By Stewart Schley

Artificial intelligence has a chance to improve on an error-riddled aspect of modern-day television: the on-screen caption

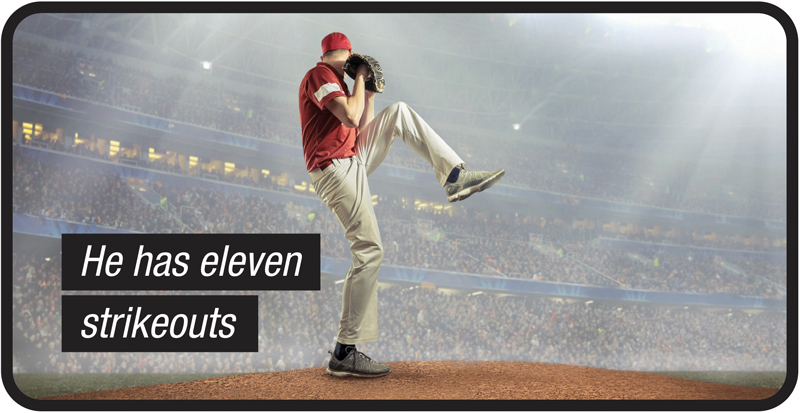

The message glowing on the screen exuded an ominous vibe, as if it could be a coded warning about an imminent alien invasion: “HE’S HASEVESTRIKEOUTS.”

Thankfully, it turned out to be nothing so threatening. Instead, it was a typed caption appearing during an interlude of a Major League Baseball game (Rockies at Marlins) televised earlier this season by AT&T’s SportsNet Rocky Mountain network. The misstated verbiage means one of two things probably happened. One possibility is that a hurried stenographer mis-typed whatever the play-by-play announcer had uttered from the broadcast booth, producing an indecipherable mis-mash. (Our best guess: “He has eleven strikeouts.”) The other is that an automated content recognition platform took in the announcer’s speech and did the best it could to spit out a comprehensible rendition, in this case falling short.

Both are excusable errors, given the near-impossible task asked of human captioning specialists and automated captioning systems alike. Blend a torrent of spoken words with the mandate to produce a real-time cascade of typed sentences and the results are bound to miss the strike zone here and there.

Except maybe not for much longer. Some enthusiasts think a new approach to video captioning that involves machine learning might finally help to achieve a long-promised wonderland where nearly flawless presentation of words and sentences is twinned with lower costs of output.

Repeat performance

Forgive video operations veterans for that sigh of fatigue you just heard in the background. They’ve seen this movie before, with preceding generations of technology that promised but failed to accomplish the same feats. Ever since the public TV station WGBH-TV in Boston aired the first known instance of “closed captioning” in 1972, inventive people with computers and microphones have tried to figure out alternatives to having a manual stenographer listen and type. Automated content recognition (ACR) techniques that attempt to translate speech to subtitles appearing on screens have been around for several decades, but still stumble around nuances of verbal expression, making for sometimes-laughable interpretations of what somebody said.

What might be new this time around, though, is the convergence of speech-to-text transcription with data-infused learning algorithms that could legitimately introduce accuracy and efficiency beyond what previous attempts have eked out. In other words, the smart machine is coming.

Artificial intelligence

The big driver here is artificial intelligence, meaning (in this case) the ability of a machine not only to hear and translate spoken words into text, but to apply human-like learning skills to the tricky task of understanding what somebody just said. Or tried to say. Emerging AI platforms optimized for captioning are armed with new toolsets such as custom acoustic models that make allowances for regional dialects and background noises, and vocabulary-extending databases that help make reasoned choices about words by examining their surrounding context.

These enhancements mean AI-infused caption systems have potential not just to transcribe speech quickly into text form, but to interpret and understand information over time to become better at what they do. In other words, they learn. That means recognizing nuances such as the difference between “fault” in a tennis match and “fault” in a news broadcast about a legal squabble.

Artificial intelligence has a chance to succeed where previous captioning-automation platforms have struggled because it creates output that more closely tracks the intention and purpose of human speech. Because of their ability to examine and interpret, AI captioning platforms work in almost the same way human transcription specialists do. Except they’re faster.

The possibility of efficiency gains in captioning is just one of many contributions AI might make to the video ecosystem. Writ large, the technology has potential to improve the way cable companies and networks do things like discern viewing tastes, cobble together precision-targeted advertising insertions and catalog video library clips by granular reference points for quick access. (“Hey kid,” bellows the hurried news director. “I need seven speech excerpts where the governor talks about holding the line on infrastructure spending, pronto!”) Some believers think AI has promise for advancing the state-of-the-art around viewing preferences and recommendations. By incorporating a broad set of inputs (social media comments, the emotive tones of scenes, even the prevailing weather conditions outside), AI may help serve up more appropriate content choices than today’s relatively coarse instruments — thumbs up and/or “like” buttons, for example — can muster.

This is the heart of the AI promise: to take enormous amounts of information and very quickly decipher interesting findings from them. Media — video in particular — is an obvious AI target because it’s basically all information: from the brightness and color tone of an individual screen pixel to the words spoken during a soccer game to the starring cast of a 2007 movie, video content can be reduced to discrete elements, run through the blender and evaluated, compared and refashioned to the nth degree.

But it has to start somewhere, and with budgets strained in a much-disrupted television sector, captioning might just be the place to grab a toehold. Today an accepted barometer is a cost of $3-$5 per minute for live program captioning, or $1-$2 per minute for non-linear/on-demand content where time pressures aren’t so severe. If AI can match those numbers or beat them while introducing accuracy improvements and better contextual understanding, there’s a good chance video operations groups will buy in.

From that toehold, AI has room to grow in the cable industry and elsewhere. Inventive business ideas include using AI to build on-the-fly, personalized highlight reels from somebody’s favorite NFL player, for example, with monetization coming from micro-transactions (“99 cents for the complete Aaron Rodgers Hail-Mary touchdown pass catalogue!”), advertising and subscription models.

But captioning alone presents a hearty market opportunity. The global market research firm MarketsandMarkets projects a compounded annual growth rate of 27.2% through 2021 for automated content recognition technology in the media and entertainment sector, with audio fingerprinting, watermarking and content recognition among the early pursuits.

Much has been written lately about the budding romance between artificial intelligence and the video industry, with grandiose ideas about how AI will make advertising smarter and recommendation engines more useful. But the first point of entry may be much more mundane, surrounding workmanlike duties around better ways to apply subtitles to screens. If nothing else, AI will make us all better readers. And vanquish any worries we might have about aliens invading during a baseball game.

Stewart Schley,

Stewart Schley,

Media/Telecom Industry Analyst

stewart@stewartschley.com

Stewart has been writing about business subjects for more than 20 years for publications including Multichannel News, CED Magazine and Kagan World Media. He was the founding editor of Cable World magazine; the author of Fast Forward: Video on Demand and the Future of Television; and the co-author of Planet Broadband with Dr. Rouzbeh Yassini. Stewart is a contributing analyst for One Touch Intelligence.

credit: Shutterstock.com