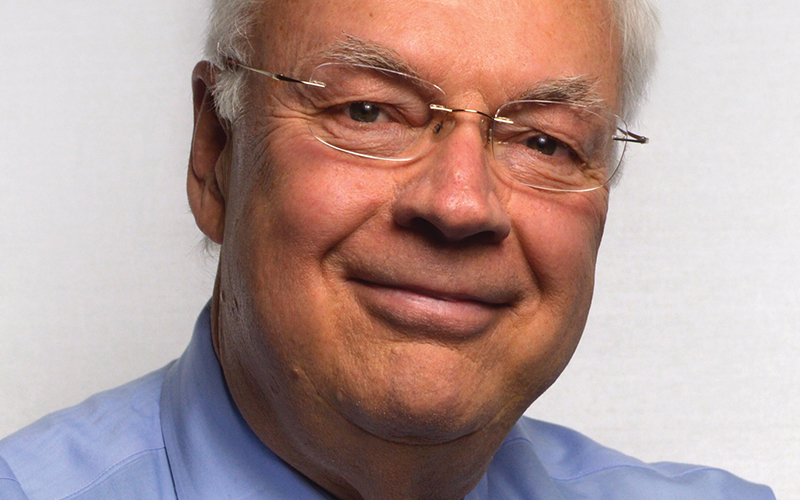

Mark Dzuban Finds His Voice

By Stewart Schley

The President and CEO of SCTE•ISBE talks about technology, leadership, Susan Sarandon, and why he’s not a huge fan of the Flat Earth Society

Mark Dzuban’s parents were concerned. The kid spent inordinate amounts of time in the basement, brewing up chemistry set concoctions that occasionally made the whole house reek. Plus, there was the scavenging thing: Pulling a Red Flyer wagon around streets of Edison, N.J. on garbage day, he kept coming home loaded up with the debris of left-for-dead components: a length of copper wire here, a tube there. Dzuban would carry his haul downstairs and busy himself for hours in the cellar with screwdrivers and a soldering gun, turning one man’s trash into the stuff of an adolescent’s electronic treasure.

“I was a nerd in the basement,” Dzuban says. “My parents complained I was constantly making the lights dim and blowing fuses. So, they figured they had to get me out of the basement for the better good of the family.”

The remedy Dzuban’s parents hit on was a tried-and-tested one: high school speech and debate class. Get Dzuban in front of a crowd, went the idea. Have him mix with some of the theater types.

It might not have worked except for the coaching of an upperclassman who took Dzuban under her wing, convincing him he had what it takes to become an able communicator. That student, Susan Tomalin, is better known by her stage name: Sarandon. Years later, when Dzuban’s son contacted Sarandon asking for proof of dad’s proclaimed high school kinship, the actress responded with a hand-written note of affirmation — and sent her regards to Dzuban. It was a reminder that the guy had a way of leaving an impression.

Unmistakable imprint

This has pretty much been the case all along, as Dzuban, now 72, has stamped an unmistakable imprint across the modern telecommunications firmament. He went from building makeshift signal amplifiers with his father to working for the TV maker Westinghouse to manufacturing line amps for the equipment firm Vikoa, a job that introduced Dzuban to a growing industry called cable television. Dzuban later went on to bid on municipal franchises and build out cable systems in New Jersey for Clear Cable of Toms River, and later for Cross Country Cable, where Dzuban began a long career association with the industry legend John Malone, CEO of Tele-Communications Inc.

In the 1980s, a flashpoint moment came as Dzuban, managing the Paterson, N.J., cable franchise for Cross Country, oversaw a trial to use the cable system to manage traffic signal communications. The experiment worked beautifully, producing error-free transmission. Impressed by the outcome, Dzuban began to consider that the difference between shuttling traffic light information and shuttling telephone calls over a cable network was…not much. “I’m saying to myself, hold on: It doesn’t make any difference if it’s a traffic control system or computer interface or something else,” Dzuban recalls. “Voice is data.”

The curiosity about what was then an untested idea led Dzuban to become an early evangelist for the voice-over-cable dream. He began to meet with the Morgan Stanley & Co. investment analyst George Kelly, making the case for voice revenues as part of a changing valuation equation for cable. In England, where Dzuban was enlisted to help develop new cable systems, he helped U.K. regulators shape new technical and service requirements for a cable-telephony pairing. It was there that colleagues took interest in a modem schematic Dzuban had sketched out, and suggested Dzuban ship his creation to Bell Labs headquarters.

Two weeks later, Dzuban got a call asking if he’d be willing to lead a team of developers to try to make it work. This was 1991. Dzuban joined the Bell Labs technical team, meeting a one-year deadline to prove out the concept, and in doing so, overcoming deep skepticism from some Bell Labs veterans. “They’d say, ‘the cable industry is not a good partner,’ or ‘the technology does not work,’ or ‘you can never put carrier level services on these networks,’” Dzuban recalls. “So my job was to say, ‘Hey, I think I can do that. So they gave me funding, they gave me resources, and at the end of the year, we proved it worked.”

Dzuban’s pioneering work in the nascent voice-over-cable arena led to a job with AT&T, which would embrace the Bell Labs work as a linchpin for its determination to plunge into the cable business by acquiring TCI and its peer company MediaOne. Until 2001, Dzuban was Senior Vice President, Telephony Engineering & Operations for AT&T Broadband, responsible for leading the rollout of circuit-switched voice services across what was then the nation’s largest cableco.

Later, with the voice-over-cable revolution gaining momentum, Dzuban rose to prominence as Vice Chairman of a bellwether technology company, Cedar Point Communications. Its early-era circuit-switched voice systems helped pave the way for what is cable’s multi-billion-dollar IP voice category today. In the space of a few years, he had gone from almost a lone champion of voice services over cable to one of the category’s biggest influencers.

Since 2014, Dzuban has taken a career’s worth of skills, knowledge, contacts and reputation and translated them to the broader industry arena as the President and CEO of SCTE•ISBE, where he has led a revitalization effort that involves stepped-up training investments, deeper alliances with industry partners, a prolific technical standards program, and an invigorated Cable-Tec Expo, the annual conference and trade show that brings thousands of industry engineers and technologists together.

Dzuban recently accepted an offer from the board to re-up for another five-year term. We spoke with him in July about where SCTE•ISBE is going, and why cable’s still the place to be. (The conversation is edited in some instances for brevity.)

You’ve had by any measure a successful, fruitful career. Why are you still working?

I like to work. My business is also my personal interest, so it’s not like I’m forced to go to work every day. It’s also in my family’s DNA. I’m 72 now, so my intent is to work another five years. Plus, my cardiologist is one of my best coaches: I had a heart valve replaced a couple of years ago — I was born with a heart murmur — and he said the best thing you can do is keep on working. Because if you become a couch potato or lethargic, it actually erodes your life expectancy.

What was your introduction to the cable world?

The first introduction came from my father, in the 1950s, I was probably eight or 10. I was in the basement, building amplifiers for the first system to distribute signals in eastern Pennsylvania. The amplifiers were all hand-made, and they used traditional twin-lead signal from an antenna up on the mountain. There was a gentleman who ran a TV repair shop, and he was serving television signals to his neighbors. My father was building these amplifiers, and I was a kid, sitting on the cellar steps, watching him drill the holes, punch it, solder everything up. My father would say every once-in-a while, ‘I need a resistor — a 22K resistor,’ and I’d be digging through the box to find the right resistor. I was kind of like the leg man for helping him to build stuff. So that was the first understanding of cable.

Later, you worked for Westinghouse and then an equipment maker, Vikoa. What did you learn?

With Vikoa, my first job was to build solid-state equipment and replace tube equipment. I had a background in solid-state technology and design, so I built some of the first line extenders and participated in some of the first solid-state Vikoa distribution equipment. It was going from 12-channel equipment to 21-channel to 36-channel capacity while I was there.

You were a tinkerer from the beginning, though.

From day one. Absolutely. When I was a kid, I made money in a couple of different ways. One was, I used to trap muskrats. That was pretty profitable. But on garbage day, I would go around with my wagon — an American Flyer wagon — and I would look for copper and other metals I could sell. And in the process of doing that, I would find a TV-chassis, and I had my pliers and I’d cut the parts out and take what I could use from the garbage.

Let’s fast-forward to voice. What originally inspired you to think about using cable to transmit telephone calls?

I am not a member of the Flat Earth Society. When Columbus left port, the gentry of the time in science and technology, the purists, said the earth is flat, and he was going to fall off the end of the earth. And then you had one character — he probably ended up as the DNA for a cable guy — who said, ‘Hold on a second: If I look closely, I can actually see the curvature of the earth. The theorem that you can’t do this is wrong.’

How does that relate to running voice over cable?

What happens is most innovation is throttled either by self-imposed obstacles, or there’s just a belief that it can’t happen. So, what happened was, we were doing a lot of work around the return path, putting data on the network, and I’m saying to myself, ‘Hold on: Voice is data.’ The only thing is that with analog it’s a little different, but it’s fundamentally data. It doesn’t make any difference if it’s a traffic control system or computer interface or something else. Voice is data.

You traveled to England in the late 1980s to work on a scheme for implementing hybrid cable-telco networks. What happened?

While I was there, I drew a schematic of a modem and showed it to the guys who were in the AT&T submarine cable group, running a cable from France to England for a franchise we’d just won. They said, ‘Would you mind if we showed this to some people at Bell Labs in Holmdel (N.J.)?’ So, in two weeks I get a note back from Bell Labs: ‘Hey, we’d like to talk to you more about your schematic’.’ I went to Holmdel and started a new division. The fundamental objective was: How can AT&T recreate carrier-like services like telephone over cable networks? And that was the genesis of their program. I ran the first division, started AT&T Broadband with (Comcast President, Technology & Product) Tony Werner. That’s how voice on cable launched.

What was gratifying about that time?

It was energizing; it was the excitement of doing something new. But it was a team effort. The greatest asset anybody can have in terms of driving these programs is creating allies. Within AT&T, Bob Stanzione (now Executive Chairman of Arris Corp.) was a partner of mine at Bell Labs who facilitated proving the concept so that we could convince the rest of AT&T the concept could work. Building advocates to support the notion is half the battle.

And the rest is…history?

After we launched the concept it became the trigger for AT&T to acquire TCI, which became AT&T Broadband. Once we had that launched, and we had about half a million subscribers on board, I started a company called Cedar Point, which was building the equivalent of an analog IP switch. We built the equivalent of a switch that was once 20,000 watts in 5,000 square feet in one cubic meter, generating 1,000 watts.

Along the way you must have dealt with some severe obstacles. How do you deal with resistance to innovation?

One of the greatest obstacles you have are the naysayers, and those who have self-imposed obstacles by just clinging to theorems they believe are true. Whereas the folks who have good intuition around innovation say, ‘You know, I know that’s the theorem, but there’s another way to build this mousetrap.’ So, I guess I’ve learned, and maybe it’s a personality trait that has developed, to go back and say, ‘I see some alternative data here that could make sense,’ and then here again, you look to the advocates.

Your career parallels that of some senior cable industry executives in that you’ve done time out in the field, on the poles, in the trenches — and in your case in the basement. Why is that meaningful?

I’ve had a chance to see very large corporations where the style is, they’re going to hire the Harvard guys who never got their hands dirty. But education is a tool; it’s not the end state. The end state is to leverage the tools to create value. If you look at our industry, most of our senior folks…just about every one of the senior CTOs and even many of our CEOs, have had their hands dirty in the field. They understand the technology, how it evolves, and how to best manage the capital, the operations and the oversight to optimize that business. We have a unique industry in that way. Because we can envision how it goes together, how it works, what are the pitfalls.

You were stationed in Korea for two years as a young man. What did it teach you?

I’m from a family on my father’s side that are Tatars, from Ukraine. It’s a military culture where all the men join the service. I joined the U.S. Army when I was 18. Volunteered. They sent me to Korea. I served in the DMZ and at 8th Army headquarters, which was combat logistics: How do you prepare for a North Korean attack? I learned a lot, had the best generals and officers, people at the table who were brilliant in addressing the things they needed to think about today, and things they needed to think about tomorrow; and especially, unintended consequences. The discipline around it was unbelievable. To this day I think about it as hugely instrumental.

How is it that Expo, in a moribund trade show environment, is still a thing?

One reason is the support of our industry and our engagement. I know all the CEOs personally, we engage with close to 20,000 members, we’re a product of them collaborating with us. We’re the embodiment of a lot of people, people who are very passionate around what we do. We are the last surviving entity that can collectively get together and ask where we are, and what we can do to continue to lead the business.

What’s your big goal in leading SCTE•ISBE?

If you look at what we do, and the environment I like to create, it’s about not getting at a comfort level, or just kicking back and watching the machine go. This is something our industry is very good at: What do we need to do to continue being agile, to keep ahead of the market, because we know things won’t develop perfectly. You may focus on 10 things and only some will mature. What’s the next step? What can we do better, smarter?

Some examples, please?

One example is, we’re looking at aging-in-place. How does the industry position our communications infrastructure to be consistent with emerging architectural design? Or, how do we become supporting of autonomous vehicles, and of the Internet-of-Things environment, of enhancing 3D wireless coverage? There are so many exciting things to work on. If you’re really into this stuff, it’s never ending. It’s always a new set of opportunities.

You support thousands of technicians, installers, engineers. Why is cable a good place for young people to be?

If I look at the evolution of our industry, today we are a major communications channel for just about all the Internet traffic, including backhaul for cellular, so our growth is going to be a continuum. And look at the expanding applications; not only today, if you look at gaming and IoT area, but going forward. If it’s a labor of love, and you can excel and become an expert, that’s where the opportunities are. We have a great industry that has a huge amount of potential we’re continuing to tap. It’s important to have the enthusiasm, and the folks who are resilient, and can continue to work through. The challenges are not all wins, right? It’s exploring. Sometimes you find dead ends, but what you learn sends you in the right direction to get to the results. It’s just never-ending. It’s a self-propelling engine.

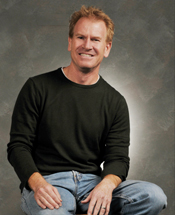

Media/Telecom Industry Analyst

stewart@stewartschley.com

Stewart has been writing about business subjects for more than 20 years for publications including Multichannel News, CED Magazine and Kagan World Media. He was the founding editor of Cable World magazine; the author of Fast Forward: Video on Demand and the Future of Television; and the co-author of Planet Broadband with Dr. Rouzbeh Yassini. Stewart is a contributing analyst for One Touch Intelligence.